WEYLAND/VÖLUNDR - THE SMITH: A PAN-GERMANIC LEGEND OF THE MASTER BLACKSMITH

- Hrolfr

- Sep 20, 2025

- 14 min read

Weyland the Smith – known as Völundr in Old Norse and Welund in Old English – is a legendary blacksmith whose tale spans the Norse, Anglo-Saxon, and broader Germanic worlds.

His story is one of skill, suffering, vengeance, and escape. Enslaved by a cruel king, the master-smith plots a gruesome revenge and then flies to freedom with a set of wings he forges himself – an uncanny parallel to Daedalus in Greek faith myth. References to Weyland appear in diverse sources: a complete Norse poem in the Poetic Edda, an episode in a medieval saga, cryptic lines in an Old English lament, and even carved illustrations on ancient artifacts. The consistent core across these traditions portrays Weyland as an extraordinary craftsman wronged by royalty, who retaliates in dramatic fashion before vanishing into legend.

Below, we explore the story’s major versions and historical depictions, drawing on key sources from Norse faith and myths, Anglo-Saxon literature, and continental lore.

The Tale in Norse Faith: Völundarkviða (The Lay of Völundr)

In Norse tradition, Weyland’s story is told most fully in Völundarkviða (“The Lay of Völundr”), one of the poems of the Poetic Edda. This Old Norse poem recounts how Völundr (Weyland) and his two brothers, Slagfiðr and Egil, dwelled in the wild until they encountered three enchanting swan-maidens (Valkyries) on a lake shore.

Völundr married one of these maidens, and when she later flew away, he remained behind waiting for her return, crafting golden rings in her memory. The heart of the story begins when King Níðuðr of Närke (in Sweden) learns of Völundr’s renowned skill and captures him in his sleep. To prevent the smith’s escape, the king cruelly hamstrings Völundr (cutting the tendons of his legs) and imprisons him on an island called Sævarstöð, forcing him to forge treasures for the king’s family. Níðuðr claims Völundr’s prized sword for himself and gives Völundr’s wife’s ring to his own daughter, Böðvildr. Consumed by grief and fury, the crippled smith secretly plots revenge while outwardly toiling at his forge.

In a grim turn, Völundr lures Níðuðr’s two young sons to his workshop, murders them, and conceals their bodies. Demonstrating his dark craft, he then refashions the boys’ remains into artifacts: he turns their skulls into ornate goblets, their eyes into gleaming jewels, and their teeth into a brooch. Völundr sends these macabre gifts to the king and queen, who do not suspect their true origin. Next, when Princess Böðvildr brings Völundr the broken ring (once his wife’s) to repair, the smith uses the opportunity to violate her – he drugs her with beer and impregnates her, adding personal humiliation to the king’s forthcoming tragedies.

Finally comes Völundr’s dramatic escape. Over time he gathered feathers from birds (in some versions aided by his brother Egil, a skilled archer) and crafted himself a feathered flying cloak or wings. Rising into the air, Völundr flies to the king’s hall and, hovering above out of reach, taunts King Níðuðr by revealing the full extent of his deeds: he gleefully announces that the king is drinking from his own sons’ skulls and that Böðvildr is carrying his child. The weeping king cries out in despair, realizing none of his archers or warriors can shoot the flying smith down. Böðvildr is summoned and tearfully confesses she could not defend herself against Völundr’s strength. Völundr thus escapes unpunished, flying off “never to be seen again,” while the king is left to face his family’s ruin. The Völundarkviða ends on this somber note of vengeance fulfilled.

Notably, the poem’s opening and prose epilogue hint at Völundr’s earlier life and wider fame. They reference his time with the swan-maiden wife and even identify Völundr as “prince of the Elves,” suggesting his almost supernatural skill. The Norse compiler of Völundarkviða was likely drawing on older legends common to many Germanic peoples, as the language shows influence from Old English and the story itself was probably borrowed from Saxon (Germanic) tradition. Indeed, as we see next, the figure of Weyland/Welund was already well-known in Anglo-Saxon England centuries before the Norse poem was written.

Anglo-Saxon Echoes: Welund in Old English Poetry

By the Early Middle Ages, the legend of Weyland/Welund was firmly embedded in Anglo-Saxon lore. Although no full Old English narrative survives, a few tantalizing references prove the story’s currency in England. The most famous is in the Old English poem “Deor” (10th century), where the poet laments his sorrows by comparing them to the trials of legendary figures. The opening lines allude directly to Welund’s anguish:

“Welund him be wurman wræces cunnade” – “Welund, for his sins (or among serpents), knew exile and hardship.”

These lines portray Welund’s torment in captivity, likely referencing his imprisonment by Niðhad (the Old English name for Níðuðr) and the suffering he endured after being hamstrung. The poem also mentions Beadohild (Böðvildr):

“Beadohilde ne wæs hyre broþra deaþ on sefan swa sār, swā hyre sylfre þing, þæt hēo gearolīce ongieten hæfde þæt hēo ēacen wæs.” – “Beadohild did not feel as sorrowful for her brothers’ death as she did for her own plight, once she clearly realized that she was pregnant.”

In these stark lines, the Anglo-Saxon poet assumes the audience knows the backstory: Beadohild’s brothers have been killed (by Welund), and she is now bearing Welund’s child – an implicit reference to the rape in the smith’s revenge. The poet’s refrain “Þæs ofereode, þisses swa mæg” (“That passed away; so, may this”) suggests that even Welund’s horrific situation eventually ended. offering hope that the poet’s own troubles will also pass. Thus, in “Deor’s Lament,” Weiland’s tale of suffering, atrocity, and survival was used as a well-known exemplar of extreme woe overcome by time.

Aside from “Deor,” other Old English texts assume familiarity with Weiland’s renown as a legendary smith. In the epic Beowulf, the hero’s war-mail is described as “Weland’s work,” a superb chain-mail coat forged by Weiland. This passing reference (Beowulf, lines 450–455) attests that Anglo-Saxon audiences associated Welund with the finest craftsmanship – even without retelling his story, the poet invokes Welund to denote quality and legendary skill. Similarly, the fragmentary poem Waldere (about the hero Walter of Aquitaine) mentions a sword made by Welund, and King Alfred’s 9th-century translation of Boethius rhetorically asks, “What are the bones of Wayland, the goldsmith, now? A melancholic allusion implying that even great Wayland died and turned to dust, for all his fame.

All these references paint Welund as the preeminent mythical smith for the Anglo-Saxons, a figure whose name evoked craft excellence and tragic fate. So widespread was his legend that it even seeped into English folklore: an ancient megalithic burial mound in Oxfordshire was dubbed “Wayland’s Smithy,” with a folktale that if one left a horse overnight at the mound along with a silver coin, the unseen Wayland would shoe the horse by morning. This folk belief persisted into later centuries, illustrating how Welund/Weyland lived on as a legendary craftsman in the English imagination, long after the conversion to Christianity.

A Germanic Saga’s Version: Velent in Þiðrekssaga af Bern

Medieval Scandinavians preserved another variant of Weyland’s story in the Þiðrekssaga af Bern (“Saga of Dietrich of Bern”), a 13th-century Norwegian saga compiling continental Germanic heroic legends. In this saga – translated from lost Low German sources – Weyland appears as “Velent the Smith,” and his tale is told in a subsection often called Velents þáttr smiðs (the tale of Velent the Smith). The saga’s account aligns with the Norse Völundarkviða in broad strokes but adds many rich details and a somewhat different ending.

According to Þiðrekssaga, Velent (Wayland) was the son of a giant named Wade (Vaði) and was trained by dwarven smiths in his youth. He traveled to King Niðung’s court (Niðung corresponds to Níðuðr/Níðhad) after outsmarting his murderous dwarf teachers and even engaged in a forging contest: Velent crafted an extraordinary sword named Mímung, which proved superior by cutting through his rival smith’s iron mail. Despite Velent’s service, King Niðung eventually betrays him – breaking a promise to give Velent his daughter in marriage – which leads to Velent’s fury. After a violent incident, Niðung has Velent hamstrung and enslaved in the forge, just as in the Edda poem. Velent’s revenge in the saga is familiar: he kills Niðung’s two young sons and fashions elaborate tableware from their bones (cups from skulls, etc.), which he presents to the king. He also seduces the princess (here named Hervild or simply “the king’s daughter”) and gets her pregnant. One notable addition is the presence of Velent’s brother Egil, a great archer, whom Niðung forces to shoot an apple off his own son’s head (an episode identical to the William Tell legend). Egil secretly aids Velent: at Velent’s request, he collects bird feathers for the smith’s escape contraption and later, when Velent flies away, Egil shoots an arrow to feign hitting him, bursting a blood-filled bladder Velent had hidden under his arm – tricking Niðung into thinking the flying smith was wounded. This allows Velent to escape safely.

The saga’s conclusion diverges from the Norse poem and gives a somewhat less grim code. Velent returns to his homeland of Sjælland and, after King Niðung dies, he actually marries the princess with the new king’s blessing. Their son, called Viðga (Wittich/Widia), inherits the sword Mímung and later becomes a warrior in the service of Dietrich of Bern. (This corresponds to the wider Germanic legend in which Wayland’s son Wittich fights for King Theoderic.) Thus, the saga integrates Wayland’s family into the tapestry of heroic legends, showing Weyland not only as a figure of vengeance but also as an ancestor of heroes.

It is fascinating that the Þiðrekssaga preserves older German storytelling about Wayland. In the German poetic tradition, Wayland (Wieland) was indeed a famous smith; medieval German sources credit him with forging legendary swords like Excalibur’s cousins (for instance, the mighty swords of Charlemagne’s paladins – Durendal, Joyeuse, Curtana – were later attributed to “Wieland’s” craftsmanship in romance lore). He is also explicitly named in the Latin epic Waltharius (c. tenth century) as the smith who made Walter of Aquitaine’s armor. The saga’s mention of Wade the giant as Wayland’s father likewise reflects an English tradition (the name Wade appears in Chaucer and other sources) suggesting an even broader legendary cycle. In sum, across the Continent the figure of Wayland/Wieland was woven into various heroic narratives, underscoring his pan-Germanic fame.

Early Medieval Art: Franks Casket and Ardre Stone VIII

The most vivid testaments to Weyland’s legend in early medieval times come from art and archaeology. Chief among these is the famous Franks Casket, an Anglo-Saxon whalebone chest (early 8th century, Northumbria) intricately carved with scenes from faith and folklore and history. The front panel of this casket is divided into two halves: the right half shows the Biblical Adoration of the Magi, while the left half depicts the Germanic legend of Weyland (Welund) the Smith. In the left scene, we see Welund in his forge, held captive by King Niðhad (whose name is spelled in runes above). The carvings masterfully compress multiple moments of the story into one image. Welund is shown offering a goblet to a woman (identified by accompanying runes as Beadohild, the king’s daughter). Notably, Welund holds the goblet with tongs, and at his feet lies the headless body of Niðhad’s son – indicating that Welund has already killed the prince and crafted his skull into this very cup.. The scene even alludes to Welund’s escape: to the right, a figure (perhaps Welund’s brother or Welund himself in another moment) catches birds, foreshadowing the construction of feathered wings. The imagery is accompanied by an Old English runic inscription around the border – a riddle about the casket’s whale-bone material – which does not relate to Welund’s tale but exemplifies the casket’s intellectual complexity. The Franks Casket’s Weland panel is remarkable as an early medieval visual narrative: it explicitly highlights Welund’s cruel bondage (his hamstrung legs are hinted by his stance), his murderous revenge (the slain prince), and the pivotal moment of him tricking Beadohild with the cup of drugged beer. Carved in Northumbria around the year 700, this artwork shows the Welund story was known in Anglo-Saxon England and deemed important enough to juxtapose with Christian imagery. (Scholars have even interpreted the pairing of Welund and the Magi as a contrast between pagan vengeance and Christian redemption.) In short, the Franks Casket offers tangible, carved proof of Weyland’s cross-cultural footprint: an English artifact depicting a tale also found in Norse and Germanic verse.

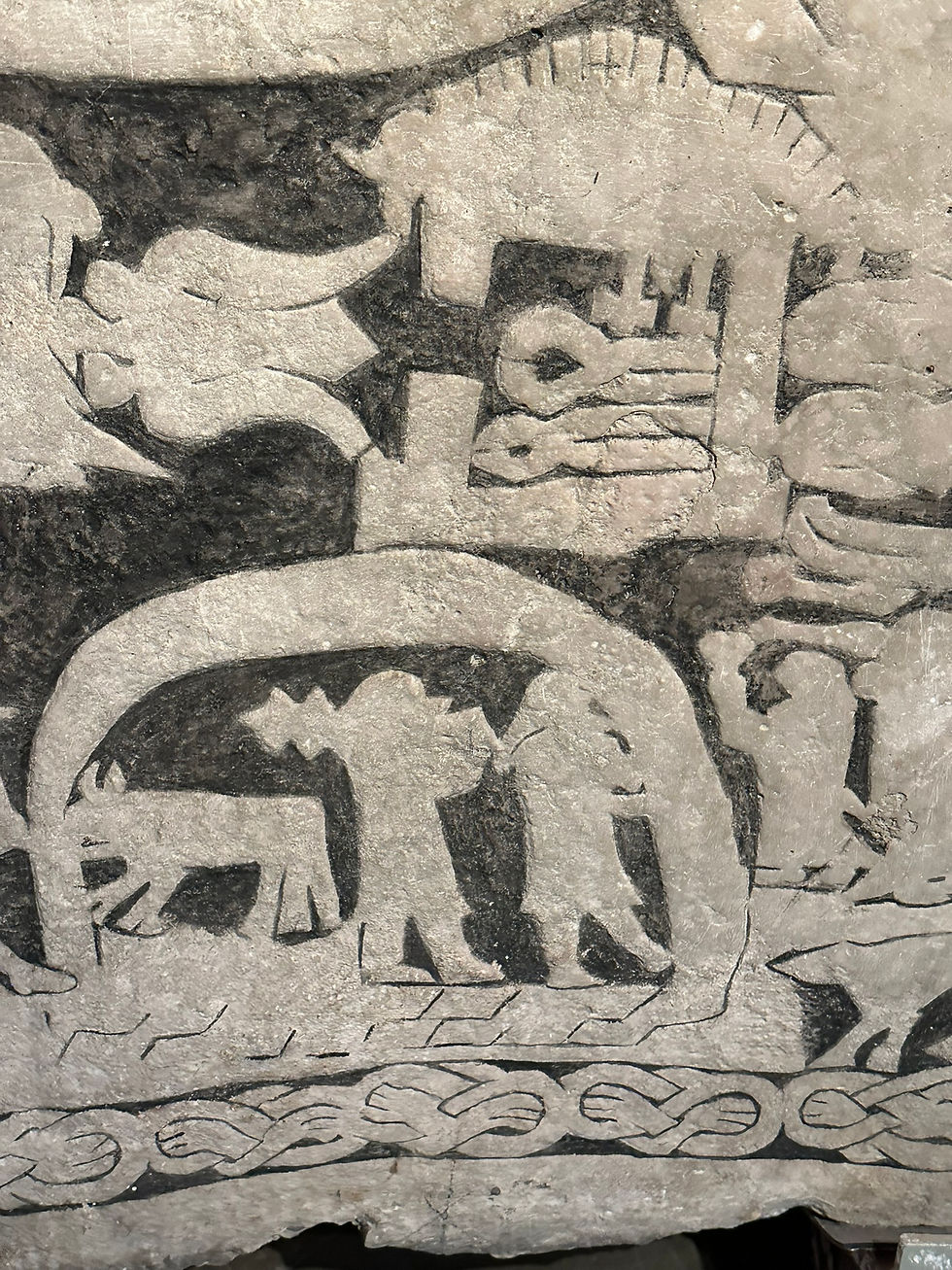

Another striking depiction comes from Ardre Stone VIII, - the Völund Stone a large picture-stone (8th–9th century) found on Gotland, Sweden. This stone is covered in carved scenes from Norse Faith, and notably it includes the Lay of Weyland the Smith among its motifs. The lower portion of the stone shows what scholars interpret as Völundr’s saga: Weyland’s forge is at the center, with a female figure (likely the princess) to one side and what appear to be concealed or dismembered bodies (the king’s sons) on the other. In one part of the carving, a human figure seems to be winged or in bird-form, flying away, which aligns perfectly with Völundr’s airborne escape. The iconography- is complex (the stone also depicts scenes of Thor, Odin on Sleipnir, etc.), but experts agree that “elements of the story of Wayland/Völundr the smith… can be seen on the Ardre VIII stone: it shows Wayland’s smithy, the decapitated corpses of the king’s sons, and the hero escaping in the shape of a giant bird.” The Ardre stone, therefore, is like a pictorial retelling of the Volundarkviða on rock. Its carvings confirm that by the Viking Age, the Völundr/Weyland legend was well known in Scandinavia – enough to be immortalized in stone on a prominent memorial. Together with the Franks Casket, it indicates that the tale had a pan-Germanic appeal, transcending language and region: from England to Gotland, artists chose Weyland’s dramatic revenge and flight as worthy subject matter.

The Chieftain recently saw the Völund Stone from Gotland, dating to around 700–800 CE. Classified as GP 21 Ardre kyrka VIII. It is 230cm wide and 20cm thick.

The Völund Stone itself is made of limestone, its back side naturally smoothed and slightly curved, like the other stones of its kind, each bearing the distinctive “mushroom” shape characteristic of Gotlandic picture stones. Today it stands proudly once more set on the stairs leading down to the museum’s Gold Room.

Its imagery is striking at the top, a horseman rides Sleipnir, unmistakably Odin. Above him hover distorted human figures, perhaps the fallen slain, headed to Valhalla. Over this scene cuts a spear in flight, aimed not only at Odin and the bird-shape of Völundr but also toward the hall-building carved below—an omen and a weapon frozen forever in stone. "Odin owns you all."

What was once silenced beneath a church floor now stands again, vibrating with power, carrying forward the voice of the saga and the faith of the North. This limestone monument preserves scenes from the Völundarkviða, the lay of Völundr the Smith, one of the most haunting sagas of the Eddas. Völundr, the master craftsman, was captured by King Niðhad, hamstrung, and forced to labor as a slave. The stone shows his smithy, with the slain sons of Niðhad lying beheaded behind it. In vengeance, Völundr crafted treasures (drinking goblets) from their remains and seduced the king’s daughter. At the center of the stone, he takes flight in bird-form, escaping on wings of his own making. Above, Odin rides Sleipnir, placing this tale within the great web of fate. A longship with full sail cuts across the middle, echoing both the life of the islanders of Gotland and the eternal voyage between worlds. Even a fishing scene rests in one corner—daily life carved alongside myth.

The stone was discovered in 1900 during the restoration of Ardre Church on Gotland, one of eight picture stones found reused beneath its floor. That such sacred images were desecrated and buried as mere foundation speaks to the violence of conversion. Yet here, restored and set upright in Stockholm, the Völund Stone speaks again.

A total of eight picture stones, that includes this one, were uncovered beneath the nave of Ardre Church on Gotland. They had been deliberately laid flat, pressed into the earth as the very floor of the Christian sanctuary. At the center of this grouping lay the Völund Stone, desecrated yet preserved by this act of sacrilege.

The first to study the discovery was Hugo Pipping, who documented the stones when they came to light during the church’s restoration in 1900. To shield them from falling plaster, the stones were placed in a shed, and news of the find quickly spread through the newspapers of the day. Scholars at the time assumed the stones had served as flooring in an earlier phase of the church, which was originally built at the end of the 11th century.

And this stone more than speaks—it vibrates. These stones carry a power that words can hardly describe. Stand before them and you feel the weight of centuries, the pulse of myth, the presence of the people who raised them. They transport you back to an older world, when memory, magic, and stone were one. They are not relics—they are living voices. They are powerful hence were hidden in a church floor or foundation, they were feared, they speak truth, they will revitalize your faith in the Old Ways.

It is worth noting that additional fragments and carvings in medieval Europe may also reference Weyland’s legend. For example, an early medieval copper-alloy mount found at Uppåkra in Sweden (c. 10th century) might depict Wayland binding or working at a forge. In England, a few stone cross-shafts (such as a fragment from Leeds) have been tentatively identified as showing scenes from Welund’s story (though such identifications are debated). And as mentioned, the Pforzen buckle from 6th-century Bavaria bears a runic inscription “Weland,” possibly invoking the smith’s name. These clues reinforce that Weyland was not an obscure figure but one that resonated widely, with his name or image popping up in artifacts across the Germanic world.

Conclusion and Legacy

Weyland the Smith’s enduring story – of a peerless craftsman-turned-avenger – offers a fascinating window into early Germanic imagination. Across Old Norse poetry, Anglo-Saxon verse, and Germanic saga, we find slightly different versions of the same gritty legend, each culture adapting it to its context. To the Norse skalds, Völundr was a tragic anti-hero, an elfin smith who suffers humiliation and responds with horrific vengeance before vanishing into the sky. To the Anglo-Saxons, Welund exemplified both supreme skill and the theme of über-heroic suffering – his name evoked wondrous artifacts and the inevitability of fate’s reversals. Continental traditions integrated Wieland into heroic genealogies, making him an ancestor of warriors and the forger of epic weapons. The archetype of the ‘crippled smith who triumphs may carry echoes of even older Indo-European tales, but in Weyland it achieved a uniquely Germanic expression: blending craftsmanship, cunning, cruelty, and a daredevil escape.

By the High Middle Ages, elements of Weyland’s story continued to reverberate in folklore and literature. In England, as noted, folk belief held that Wayland’s magic still shod horses at his ancient barrow. Romantic-era writers like Sir Walter Scott and Rudyard Kipling later reimagined Wayland in their works, ensuring the smith’s legend lived on for new audiences. Modern fantasy often nods to Wayland as the archetype of the master-smith (for instance, in J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium, the Noldorin elves’ greatest craftsman shares some of Völundr’s DNA). Yet it is the medieval evidence – the poems, sagas, and carvings – that most compellingly testify to Weyland’s impact on the cultural landscape of early Northern Europe. Weyland the Smith stands alongside figures like Sigurd the dragonslayer and Odin the wanderer as one of the great legendary characters of the Germanic world. His tale is darker and more brutal than many, but it captures the imagination with its mix of ingenious artistry and visceral revenge. Whether read in an Eddic lay, glimpsed on an ancient casket, or heard as an Anglo-Saxon minstrel’s allusion, the story of Weyland has proven to be as enduring as the metalwork he forged – a true legendary saga that transcended borders and left its mark on art, literature, and legend.

Footnotes and Further Reading:

Völundarkviða – The Lay of Völundr, in the Poetic Edda. English translation available at Sacred-Texts: Henry A. Bellows, 1936. This primary source poem (Codex Regius) recounts Völundr’s capture, revenge, and escape in Old Norse alliterative verse.

Deor – Old English poem from the Exeter Book (10th c.), which alludes to “Welund’s” suffering and Beadohild’s plight.

See Deor’s Lament (translations by Michael R. Burch or others) for the context of Welund in Anglo-Saxon elegy.

Þiðrekssaga af Bern – The Saga of Dietrich of Bern. The Wayland portion is Velents þáttr smiðs. English translation: Edward R. Haymes, The Saga of Thidrek of Bern (New York: Garland, 1988). This saga preserves the continental (Low German) version of Wayland’s story with additional episodes (Wade as father, Mimung sword, etc.).

Franks Casket – Northumbrian whale-bone casket (British Museum, 8th c.) carved with Weland’s legend. See British Museum Collection Online (Object 1867,0120.1) for images and description. Also, see M. Karkov, “The Franks Casket Speaks Back…” (Postcolonising the Medieval Image, 2017) for scholarly analysis of its iconography.

Ardre Image Stone VIII – Gotlandic picture stone (Statens Historiska Museet, Stockholm) depicting Wayland among other tales. Refer to S. Oehrl, “Wayland the Smith and the Massacre of the Innocents: Pagan-Christian Amalgamation on the Franks Casket” (2021) which also discusses the Ardre stone; and the Gotland Museum’s online database for a 3D model of Ardre VIII.

Beowulf (trans. Seamus Heaney) – Lines 450–455 reference Beowulf’s coat of mail as “Weland’s work”. This signifies how widely known Weland was as a legendary smith even in heroic epic.

Waltharius – Latin epic (10th c.) featuring “Wielandia fabrica” (Wayland’s workmanship) protecting the hero. English translation by J. M. Denton (1982) provides context on Wayland’s fame in Frankish/German traditions.

Scholarship on Weyland – For a comparative study of the legend, see Hilda Ellis Davidson, “Weland the Smith” in Folklore 68(1957): a classic article examining the figure across sources. Also, Jessie L. Weston (1901) on Wayland in romance, and Arthur Bugge (1881) for the seminal analysis of Völundarkviða’s relationship to Anglo-Saxon tradition.

Further Mythology – Weyland finds parallels in other mythic smiths (Ilmarinen in the Finnish Kalevala, Goibniu in Irish lore, etc.), and his story has been interpreted through various lenses (solar mythology, initiation rite symbolism, etc.). For an accessible overview, see the “Wayland the Smith” entry in Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed., 1911), which is now public domain and still informative.

.

Comments