NORSE LUCK AND HAMINGJA: AN EXPLORATION

- Hrolfr

- Feb 28, 2025

- 6 min read

Introduction

Luck in Old Norse culture (heill, gæfa, or hamingja in various contexts) was not a trivial or random force as it is often considered today. Instead, it was a critical component of identity and fate, deeply embedded in Norse notions of heroism, kingship, and social order. Modern English "luck" usually implies chance or fortune beyond one’s control, but the Norse concept was fundamentally different. As scholars have noted, what the sagas call heppinn (“lucky”) did not signify mere happenstance. It denoted “a quality inherent in the man and his lineage, a part of his personality similar to his strength, intelligence, or skill.” In other words, luck was an innate essence tied to a person’s character and family, at once cause and expression of their success and well-being.

This article examines the Norse concept of luck and the Old Norse term hamingja from historical, linguistic, and mythological perspectives. Key facets of this discussion include the role of luck in Norse society (especially for heroes and kings), how ancient views of luck differ from modern interpretations (drawing on the work of Bettina Sejbjerg Sommer and Vilhelm Grønbech), the various domains in which luck manifested (fertility, battle, weather, kinship), and the dual nature of hamingja as both an abstract force and a personal or familial spirit. Comparative insights will also be offered, linking Norse hamingja to analogous concepts in other cultures and faiths/mythologies. By exploring these dimensions, we can better understand how luck functioned as a legitimizing force and a unifying thread in the tapestry of Norse belief and social structure.

Ancient Norse vs. Modern Notions of Luck

The ancient Norse understanding of luck stands in stark contrast to contemporary notions. In modern thought, luck is usually seen as a random, unpredictable occurrence—being “in the right place at the right time” by chance. By contrast, in Old Norse culture luck was considered an intrinsic attribute of a person or kin group. One did not have a lucky event so much as one possessed luck as a quality. Bettina Sejbjerg Sommer (2007) emphasizes that luck for the Norse was a personal power woven into one’s character and inherited through one’s ancestors. It was stable and predictable in the sense that a person with strong luck could be expected to succeed consistently, unless that luck was lost or taken away by extraordinary means.

Vilhelm Grønbech, writing in the early 20th century, was one of the first scholars to articulate this idea, noting that “luck” in the saga ethos is akin to an innate life-force or mægn (might) that an individual carries. Misinterpreting saga language through a modern lens can thus be misleading: calling a Norse hero “lucky” in translation might imply fluke or coincidence, whereas the original meaning points to a kind of spiritual potency or favor that the hero embodies.

Sommer and Grønbech both highlight that this conception of luck is tightly bound to lineage and honor. Luck was not purely personal in the individualistic sense; it was a family possession as well, passed down through generations. A person born into a renowned clan inherited a store of luck along with wealth or reputation. Likewise, marrying into a family or aligning with a lord could bring one under the umbrella of that family’s luck.

The Significance of Luck in Norse Culture

Luck pervaded many aspects of Norse culture, but it held particular significance in realms of heroism and kingship. To be a great hero or a successful ruler in medieval Scandinavia, one needed more than skill or bravery—one needed heill (good fortune) of a nearly supernatural caliber. Sagas and historical writings frequently credit the triumphs of legendary figures to their extraordinary luck. A hero was often literally defined as “a man of luck.” This meant that his victories in battle, his escapes from danger, and even the loyalty he inspired were manifestations of an inner force of luck. The same held true for kings.

Kings were expected to be “great men of luck” who could achieve what ordinary men could not. As Sommer notes, kings in Norse tradition were distinguished by being able to extend their luck to others. This idea of the transferability of a king’s luck is crucial: a king’s followers believed that by serving him, they partook in his powerful luck, gaining success in their own endeavors.

Luck as a Legitimizing Force in Society

Luck in Norse society was not just an abstract idea but a practical mechanism of social and political legitimacy. A chief or king’s right to lead was strongly tied to the perception of his luck. In a highly competitive environment (whether among Icelandic goðar, Norwegian jarls, or Swedish kings), being seen as fortunate and favored by fate gave one a crucial edge. Followers naturally gravitated towards a leader with a strong hamingja, since aligning with him promised benefits and protection. This created a feedback loop: success bred the reputation for luck, which in turn attracted more support, leading to further success.

Hamingja: Luck as Concept and Guardian Spirit

Central to any discussion of Norse luck is the Old Norse term hamingja. This word encapsulates the Norse idea of luck, but it also carries the connotation of a guardian spirit. Etymologically, hamingja in Old Norse means “fortune” or “luck,” and in modern Icelandic it simply means “happiness, luck.” In the Norse faith in the Old Gods and sagas, however, hamingja is often personified. It was commonly believed that a person’s luck was guided by a female spirit that accompanied them through life. This spirit, also called hamingja, was responsible for a person’s good fortune and could even manifest to others.

The Norse and Germanic Tribes were also known to engage in magical practices to influence luck. Seidr, a form of Norse magic practiced primarily by Volur (plural of Volva), could be used to foresee and alter luck. Amulets, runestones, and charms were commonly employed to attract good fortune and protect against ill luck. These practices highlight the Vikings' belief in the tangible and manipulable nature of luck.

“But this turn that Steinar played was Thord's trick to make Bersi lose his luck in the fight. And Thord went along the shore at low water and found the luck-stone and hid it away.”

“The Saga of Cormac the Skald”

“Heavy the beam above the door.

Hang a horseshoe on it.

Against ill-luck, lest it should suddenly

Crash and crush your guests.”

Havamal

Luck was not only an individual matter but also a collective one. Again, the Old Norse words heill and hamingja reflect also that one’s family, clan, or even a ship’s crew was considered vital for their collective success. A leader with strong personal luck could inspire confidence and unity among his followers, contributing to the overall prosperity and victory of the group. This communal aspect of luck reinforced social bonds and cooperation. Luck was part of honor and seen as a crucial element in navigating life’s challenges and achieving greatness. It was a force to be earned, maintained, and, when necessary, enhanced through both honorable deeds and mystical means.

The lucky are also the happiest if you have noticed.

“An ill tempered, unhappy man

Ridicules all he hears,

Makes fun of others, refusing always

To see the faults in himself.”

Havamal

“Never open your heart to an evil man.

When fortune does not favor you:

From an evil man, if you make him your friend,

You will get evil for good.”

Havamal

“After this there was much talk about making ready to go to the land which Leif had discovered. Thorstein, Eirik's son, was chief mover in this, a worthy man, wise and much liked. Eirik was also asked to go, and they believed that his luck and foresight would be of the highest use.”

“Saga of Eirik the Red

“Now we may nowise allow thy lucklessness to be the bringer-about of our ruin.”

“The Story of Hrafnkell, Frey's Priest”

Conclusion

The Norse concept of luck, especially as embodied in the term hamingja, reveals a worldview in which chance and fate were domesticated into a personal asset. Far from being random, luck was something one could be born with, cultivate, share, lose, or even die from lack of. It was a cornerstone of Norse thought, binding together our faith, social structure, and individual identity. Honor was the foundation of Norse life, and luck was its companion. The fortunate were respected, their influence extending through their kin and community. The unlucky, on the other hand, often found themselves isolated unless they took deliberate steps to change their fate.

As Vilhelm Grønbech observed:

“Whichever way we turn, we find the power of luck. It determines all progress. Where it fails, life sickens. It seems to be the strongest power, the vital principle indeed, of the world.”

By choosing to associate with those who cultivate luck and honor, one ensures a path of prosperity, success, and fulfillment.

References

[1] Sommer, Bettina Sejbjerg. “The Norse Concept of Luck.” Scandinavian Studies 79, no. 3 (2007): 275-294.

[2] Grønbech, Vilhelm Peter. The Culture of the Teutons. London: Oxford University Press, 1931.

[3] Sturluson, Snorri. Heimskringla: The History of the Kings of Norway. Trans. Lee M. Hollander. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964.

[4] Davidson, Hilda R. Ellis. The Road to Hel: A Study of the Conception of the Dead in Old Norse Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968.

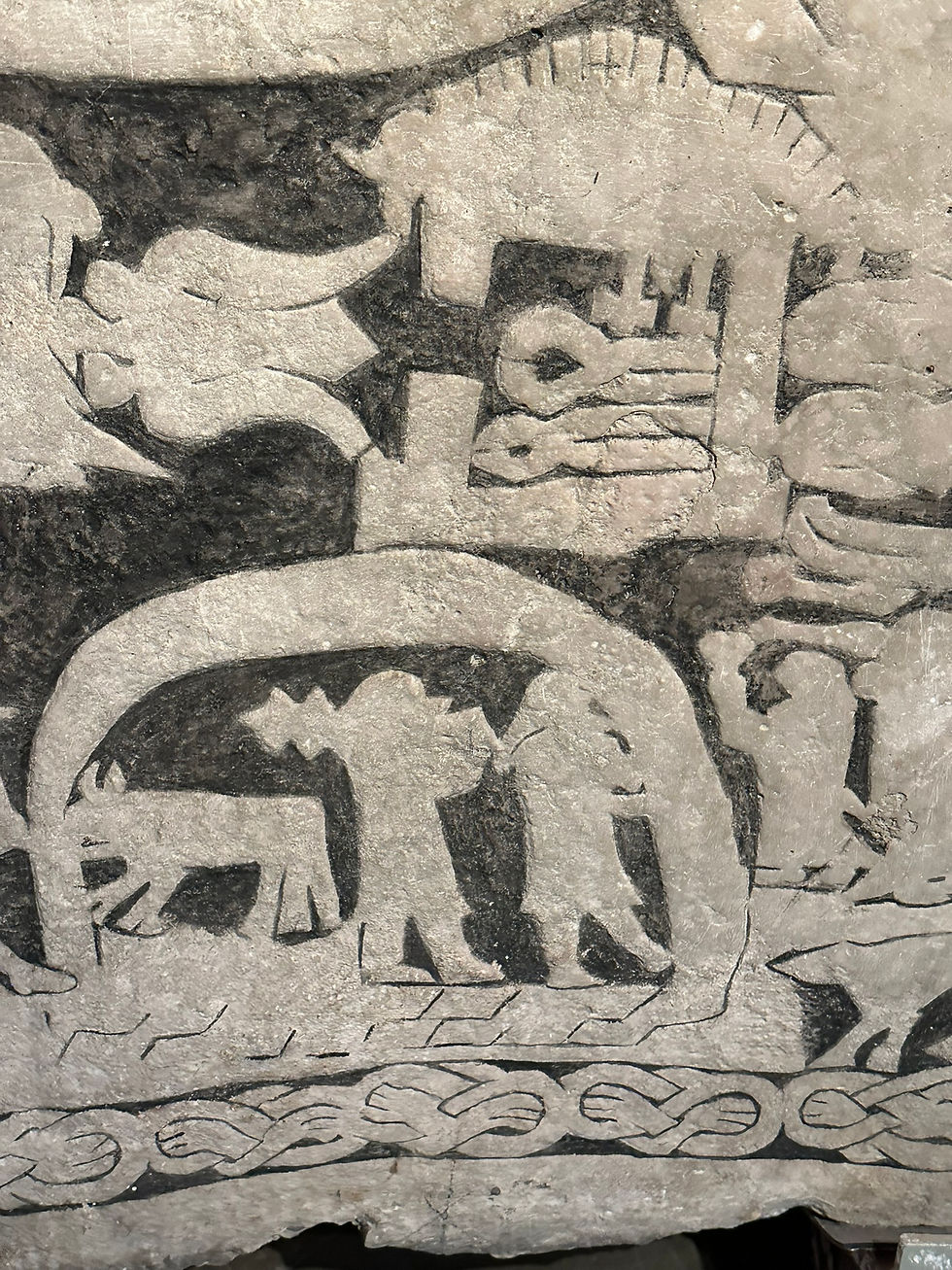

The Norns weaving

Comments